Excerpt from one of the most historically significant books of our time. Originally published in 1987:

The Chalice and the Blade: Our History, Our Future

by Riane Eisler

Introduction: The Chalice and the Blade

The contribution of feminist scholarship to a holistic study of cultural evolution -- encompassing the whole span of human history and both halves of humanity -- is more obvious: it provides the missing data not found in conventional sources. In fact the reevaluation of our past, present, and future presented in this book would not be possible without the work of scholars such as Simone de Beauvior, Jessie Bernard, Ester Boserup, Gita Sen, Mary Daly, Dale Spender, Florence Howe, Nancy Chodorow, Adrienne Rich, Kate Millett, Barbara Gelpi, Alice Schlegel, Annette Kuhn ... to name but a few. Dating from the time of Aphra Behn in the seventeenth century and even earlier, but only coming into its own during the past two decades, the emerging body of data and insight provided by feminist scholars is, like "chaos" theory, opening new frontiers for science.

The chapters that follow explore the roots of -- and paths to -- that future. They tell a story that begins thousands of years before our recorded (or written) history: the story of how the original partnership direction of Western culture veered off into a bloody five-thousand-year dominator detour. They show that our mounting global problems are in large part the logical consequences of a dominator model of social organization at our level of technological development -- hence can not be solved within it. And they also show that there is another course which, as co-creators of our own evolution, is still ours to choose. This is the alternative of breakthrough rather than breakdown: how through new ways of structuring politics, economics, science, and spirituality we can move into the new era of a partnership world.

The Chalice and the Blade: Our History, Our Future

by Riane Eisler

Introduction: The Chalice and the Blade

This book opens a door. The key to unlock it was fashioned by many people and many books, and it will take many more to fully explore the vast vistas that lie behind it. But even opening this door a crack reveals fascinating new knowledge about our past -- and a new view of our potential future.

For me, the search for this door has been a life-long quest. Very early in my life I saw that what people in different cultures consider given -- just the way things are -- is not the same everywhere. I also very early developed a passionate concern about the human situation. When I was very small, the seemingly secure world I had known was shattered by the Nazi takeover of Austria. I watched as my father was dragged away, and after my mother miraculously obtained his release from the Gestapo, my parents and I fled for our lives. Through that flight, first to Cuba and finally to the United States, I experienced three different cultures, each with its own verities. I also began to ask many questions, questions that to me are not, and never have been, abstract.

Why do we hunt and persecute each other? Why is our world so full of man's infamous inhumanity to man -- and to woman? How can human beings be so brutal to their own kind? What is it that chronically tilts us toward cruelty rather than kindness, toward war rather than peace, toward destruction rather than actualization?

Of all life-forms on this planet, only we can plant and harvest fields, compose poetry and music, seek truth and justice, teach a child to read and write -- or even laugh and cry. Because of our unique ability to imagine new realities and realize these through ever more advanced technologies, we are quite literally partners in our own evolution. And yet, the same wondrous species of ours now seems bent on putting an end not only to its own evolution but to that of most life on our globe, threatening our planet with ecological catastrophe or nuclear annihilation.

As time went on, as I pursued my professional studies, had children, and increasingly focused my research and writing on the future, my concerns broadened and deepened. Like many people, I became convinced that we are rapidly approaching an evolutionary crossroads -- that never before has the course we choose been so critical. But what course should we take?

Socialists and communists assert that the root of our problems is capitalism; capitalists insist socialism and communism are leading us to ruin. Some argue our troubles are do to our "industrial paradigm," that our "scientific worldview" is to blame. Still others blame humanism, feminism, and even secularism, pressing for a return to the "good old days" of a smaller, simpler, more religious age.

Yet, if we look at ourselves -- as we are forced to by television or the grim daily ritual of the newspaper at breakfast -- we see how capitalist, socialist, and communist nations alike are enmeshed in the same arms race and all the other irrationalities that threaten both us and our environment. And if we look at our past -- at the routine massacres by Huns, Romans, Vikings, and Assyrians or the cruel slaughters of the Christian Crusades and Inquisition -- we see there was even more violence and injustice in the smaller, prescientific, preindustrial societies that came before us.

Since going backward is not the answer, how do we move forward? A great deal is being written about a New Age, a major and unprecedented cultural transformation. But in practical terms, what does this mean? A transformation from what to what? In terms of both our everyday lives and our cultural evolution, what precisely would be different, or even possible, in the future? Is a shift from a system leading to chronic wars, social injustice, and ecological imbalance to one of peace, social justice, and ecological balance a realistic possibility? Most important, what changes in social structure would make such a transformation possible?

The search for answers led me to re-examination of our past, present, and future on which this book is based. The Chalice and the Blade reports part of this new study of human society, which differs from most prior studies in that it takes into account the whole of human history (including our prehistory) as well as the whole of humanity (both its female and male halves).

Weaving together evidence from art, archaeology, religion, social science, history, and many other fields of inquiry into new patterns that more accurately fit the best available data. The Chalice and the Blade tells a new story of our cultural origins. It shows that war and the "war of the sexes" are neither divinely nor biologically ordained. And it provides verification that a better future is possible -- and is in fact firmly rooted in the haunting drama of what actually happened in our past.

Human Possibilities: Two Alternatives

We are all familiar with legends about an earlier, more harmonious and peaceful age. The Bible tells of a garden where woman and man lived in harmony with each other and nature -- before a male god decreed that woman henceforth be subservient to man. The Chinese Tao Te Ching describes a time when the yin, or feminine principle, was not yet ruled by the male principle, or yang, a time when the wisdom of the mother was still honored and followed above all. The ancient Greek poet Hesoid wrote of a "golden race" who tilled the soil in "peaceful ease" before a "lesser race" brought in their god of war. But though scholars agree that in many respects these works are based on prehistoric events, references to a time when women and men lived in partnership have traditionally been viewed as no more than fantasy.

When archaeology was still in its infancy, the excavations of Heinrich and Sophia Schliemann helped establish the reality of Homer's Troy. Today new archaeological excavations, coupled with reinterpretations of older digs using more scientific methods, reveal that stories such as our expulsion from the Garden of Eden also derive from earlier realities: from folk memories of the first agrarian (or Neolithic) societies, which planted the first gardens on this earth. Similarly (as Greek archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos already suggested almost fifty years ago), the legend of how the glorious civilization of Atlantis sank into the sea may well be a garbled recollection of Minoan civilization -- now believed to have ended when Crete and surrounding islands were massively damaged by earthquakes and enormous tidal waves.

Just as in Columbus's time the discovery of the earth is not flat made it possible to find an amazing new world that had been there all the time, these archaeological discoveries -- deriving from what the British archaeologist James Mellaart calls a veritable archaeological revolution -- open up the amazing world of our hidden past. They reveal a long period of peace and prosperity when our social, technological, and cultural evolution moved upward: many thousands of years when all the basic technologies on which civilization is built were developed in societies that were not male dominant, violent, and hierarchic.

Further verifying that there were ancient societies organized very differently from ours are the many otherwise inexplicable images of the Deity as female in ancient art, myth, and even historical writings. Indeed, the idea of the universe as an all-giving Mother has survived (albeit in modified form) into our time. In China, the female deities Ma Tsu and Kuan Yin are still widely worshiped as beneficent and compassionate goddesses. In fact, the anthropologist P. S. Sangren notes that "Kuan Yin is clearly the most popular of Chinese deities." Similarly, the veneration of Mary, the Mother of God, is widespread. Although in Catholic theology she is demoted to nondivine status, her divinity is implicitly recognized by her appellation Mother of God as well as by the prayers of millions who daily seek her compassionate protection and solace. Moreover, the story of Jesus' birth, death, and resurrection bears a striking resemblance to those of earlier "mystery cults" revolving around a divine Mother and her son or, as in the worship of Demeter and Kore, her daughter.

It of course makes eminent sense that the earliest depiction of divine power in human form should have been female rather than male. When our ancestors began to ask the eternal questions (Where do we come from before we are born? Where to we go after we die?), they must have noted that life emerges from the body of a woman. It would have been natural for them to image the universe as an all-giving Mother from whose womb all life emerges and to which, like the cycles of vegetation, it returns after death to be again reborn. It also makes sense that societies with this image of the powers that govern the universe would have a very different social structure from societies that worship a divine Father who wields a thunderbolt and/or sword. It further seems logical that women would not be seen as subservient in societies that conceptualized the powers governing the universe in female form -- and that "effeminate" qualities such as caring, compassion, and nonviolence would be highly valued in these societies. What does not make sense is to conclude that societies in which men did not dominate women were societies in which women dominated men.

Nonetheless, when the first evidence of such societies was unearthed in the nineteenth century, it was concluded that they must have been "matriarchal." Then, when the evidence did not seem to support this conclusion, it again became customary to argue that human society was -- and always will be -- dominated by men. But if we free ourselves from the prevailing models of reality, it is evident that there is another logical alternative: that there can be societies in which difference is not necessarily equated with inferiority or superiority.

One result of re-examining human society from a gender-holistic perspective has been a new theory of cultural evolution. This theory, which I have called Cultural Transformation theory, proposes that underlying the great surface diversity of human culture are two basic models of society.

The first, which I call the dominator model, is what is popularly termed either patriarchy or matriarchy -- the ranking of one half of humanity over the other. The second, in which social relations are primarily based on the principle of linking rather than ranking, may best be described as the partnership model. In this model -- beginning with the most fundamental difference in our species, between male and female -- diversity is not equated with either inferiority or superiority.

Cultural Transformation theory further proposes that the original direction in the mainstream of our cultural evolution was toward partnership but that, following a period of chaos and almost total cultural disruption, there occurred a fundamental social shift. The greater availability of data on Western societies (due to ethnocentric focus of Western social science) makes it possible to document this shift in more detail through the analysis of Western Cultural evolution. However, there are also indications that this change in direction from a partnership to a dominator model was roughly paralleled in other parts of the world.

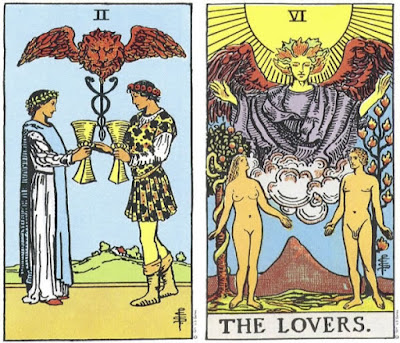

The title The Chalice and the Blade derives from this cataclysmic turning point during the prehistory of Western civilization, when the direction of our cultural evolution was quite literally turned around. At the pivotal branching, the cultural evolution of societies that worshiped the life-generating and nurturing powers of the universe -- in our time still symbolized by the ancient chalice or grail -- was interrupted. There now appeared on the prehistoric horizon invaders from the peripheral areas of our globe who ushered in a very different from of social organization. As the University of California archaeologist Marija Gimbutas writes, these were people who worshiped "the lethal power of the blade" -- the power to take rather than give life that is the ultimate power to establish and enforce domination.

The Evolutionary Crossroads

Today we stand at another potentially decisive branching point. At a time when the lethal power of the Blade -- amplified a millionfold by megatons of nuclear warheads -- threatens to put an end to all human culture, the new findings about both ancient and modern history reported in The Chalice and the Blade do not merely provide a new chapter in the story of our past. Of greatest importance is what this new knowledge tells us about our present and potential future.

For millennia men have fought wars and the Blade has been a male symbol. But this does not mean men are inevitably violent and warlike. Throughout recorded history there have been peaceful and nonviolent men. Moreover, obviously there were both men and women in the prehistoric societies where the power to give and nurture, which the Chalice symbolizes, was supreme. The underlying problem is not men as a sex. The root of the problem lies in a social system in which the power of the Blade is idealized -- in which both men and women are taught to equate masculinity with violence and dominance and to see men who do not conform to this ideal as "too soft" or "effeminate."

For many people it is difficult to believe that any other way of structuring human society is possible - much less that our future may hinge on anything connected with women or femininity. One reason for these beliefs is that in male-dominant societies anything associated with women or femininity is automatically viewed as a secondary, or women's, issue -- to be addressed, if at all, only after "more important" problems have been resolved. Another reason is that we have not had the necessary information. Even though humanity obviously consists of two halves (women and men), in most studies of human society the main protagonist, indeed often the sole actor, has been male.

As a result of what has been quite literally "the study of man," most social scientists have had to work with such an incomplete and distorted data base that in any other context it would immediately have been recognized as deeply flawed. Even now, information about women is primarily relegated to the intellectual ghetto of women's studies. Moreover, and quite understandably because of its immediate (though long neglected) importance for the lives of women, most research by feminists has focused on the implications of the study of women for women.

This book is different in that it focuses on the implications of how we organize the relations between the two halves of humanity for the totality of a social system. Clearly, how these relations are structured has decisive implications for the personal lives of both men and women, for our day-to-day roles and life options. But equally important, although still generally ignored, is something that once articulated seems obvious. This is that the way we structure the most fundamental of all human relations (without which our species could not go on) has a profound effect on every one of our institutions, on our values, and -- as the pages that follow show -- on the direction of our cultural evolution, particularly whether it will be peaceful or warlike.

If we stop and think about it, there are only two basic ways of structuring the relations between the female and male halves of humanity. All societies are patterned on either a dominator model -- in which human hierarchies are ultimately backed up by force or the threat of force -- or a partnership model, with variations in between. Moreover, if we reexamine human society from a perspective that takes into account both women and men, we can also see that there are patterns, or systems configurations, that characterize dominator, or alternatively, partnership, social organization.

For example, from a conventional perspective, Hitler's Germany, Khomeini's Iran, the Japan of the Samurai, and the Aztecs of Meso-America are radically different societies of different races, ethnic origins, technological development, and geographic location. But from the new perspective of cultural transformation theory, which identifies the social configuration characteristic of rigidly male-dominated societies, we see striking commonalities. All these otherwise widely divergent societies are not only rigidly male dominant but also have a generally hierarchic and authoritarian social structure and a high degree of social violence, particularly warfare.

Conversely, we can also see arresting similarities between otherwise extremely diverse societies that are more sexually equalitarian. Characteristically, such "partnership model" societies tend to be not only much more peaceful but also much less hierarchic and authoritarian. This is evidenced by anthropological data (i.e., the BaMbuti and the !Kung), by contemporary studies of trends in more sexually equalitarian modern societies (i.e., Scandinavian nations such as Sweden), and by the prehistoric and historic data that will be detailed in the pages that follow.

Through the use of the dominator and partnership models of social organization for the analysis of both our present and our potential future, we can also begin to transcend the conventional polarities between right and left, capitalism and communism, religion and secularism, and even masculinism and feminism. The larger picture that emerges indicates that all the modern, post-Enlightenment movements for social justice, be they religious or secular, as well as the more recent feminist, peace, and ecology movements, are part of an underlying thrust for the transformation of a dominator to a partnership system. Beyond this, in our time of unprecedentedly powerful technologies, these movements may be seen as part of our species' evolutionary thrust for survival.

If we look at the whole span of our cultural evolution from the perspective of cultural transformation theory, we see that the roots of our present global crises go back to the fundamental shift in our pre-history that brought enormous changes not only in social structure but also in technology. This was the shift in emphasis from technologies symbolized by the Blade: technologies designed to destroy and dominate. This has been the technological emphasis through most of recorded history. And it is this technological emphasis, rather than technology per se, that today threatens all life on our globe.

There will undoubtedly be those who will argue that because in prehistory there was a shift from a partnership to a dominator model of society it must have been adaptive. However, the argument that because something happened in evolution it was adaptive does not hold up -- as the extinction of the dinosaurs so amply evidences. In any event, in evolutionary terms the span of human cultural evolution is far too short to make any such judgment. The real point would seem to be that, given our present high level of technological development, a dominator model of social organization is maladaptive.

Because this dominator model now seems to be reaching its logical limits, many men and women are today rejecting long-standing principles of social organization, including their stereotypical sexual roles. For many others these changes are only signs of systems breakdown, chaotic disruptions that at all costs must be quelled. But it is precisely because the world we have known is changing so rapidly that more and more people over ever larger parts of this world are able to see that there are other alternatives.

The Chalice and the Blade explores these alternatives. But while the material that follows shows that a better future is possible, it by no means follows (as some would have us believe) that we will inevitably move beyond the threat of nuclear or ecological holocaust into a new and better age. In the last analysis, that choice is up to us.

Chaos or Transformation

The study on which The Chalice and the Blade is based is what social scientists call action research. It is not merely a study of what was, or is, or even of what can be, but also and exploration of how we may more effectively intervene in our own cultural evolution. The rest of this introduction is intended primarily for the reader interested in learning more about this study. Other readers may want to go straight to chapter 1, perhaps returning to this section later.

Until now, most studies of cultural evolution have primarily focused on the progression from simpler to more complex levels of technological and social development. Particular attention has been paid to major technological shifts, such as the invention of agriculture, the industrial revolution, and, more recently, the move into our postindustrial or nuclear/electronic age. This type of movement obviously has extremely important social and economic implications. But it only gives us part of the human story.

The other part of the story relates to a different type of movement: the social shifts toward either a partnership or a dominator model of social organization. As already noted, the central thesis of Cultural Transformation theory is that the direction of the cultural evolution for dominator and partnership societies is very different.

This theory in part derives from an important distinction that is not generally made. This is that the term evolution has a double meaning. In scientific parlance, it describes the biological and, by extension, cultural history of living species. But evolution is also a normative term. Indeed, it is often used as a synonym for progress: for the movement from lower to higher levels.

In actual fact, not even our technological evolution has been a linear movement from lower to higher levels, but rather a process punctuated by massive regressions, such as the Greek Dark Age and the Middle Ages. Nonetheless, there seems to be an underlying thrust toward greater technological and social complexity. Similarly, there seems to be a human thrust toward higher goals: toward truth, beauty, and justice. But as the brutality, oppression, and warfare that characterize recorded history all too vividly demonstrate, the movement toward these goals has hardly been linear. Indeed, as the data we will examine documents, here too there has been massive regression.

In gathering the data to chart, and test, the social dynamics I have been studying, I have brought together findings and theories from many fields in both the social and natural sciences. Two sources have been particularly useful: the new feminist scholarship and new scientific findings about the dynamics of change.

A reassessment of how systems are formed, maintain themselves, and change is rapidly spreading across many areas of science, through works such as those of Nobel Prize winner Ilya Prigogine and Isabel Stengers in chemistry and general systems, Robert Shaw and Marshall Feigenbaum in physics, and Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela in biology. This emerging body of theory and data is sometimes identified with the "new physics" popularized by books such as Fritjof Capra's Tao of Physics and The Turning Point. It is sometimes also called "chaos" theory because, for the first time in the history of science, it focuses on sudden and fundamental change -- the kind of change that our world is increasingly experiencing.

Of particular interest are the new works investigating evolutionary change by biologists and paleontologists such as Vilmos Csanyi, Niles Eldredge, and Stephen Jay Gould, as well as by scholars such as Erich Jantsch, Ervin Laszlo, and David Loye on the implications of "chaos" theory for cultural evolution and social science. This is by no means to suggest that human cultural evolution is the same as biological evolution. But although there are important differences between the natural and social sciences, and the study of social systems must avoid mechanistic reductionism, there are also important similarities regarding both systems change and systems self-organization.

All systems are maintained through the mutually reinforcing interaction of critical systems parts. Accordingly, in some striking respects the Cultural Transformation theory presented in this book and the "chaos" theory being developed by natural and systems scientists are similar in what they tell us of what happened -- and may now again happen -- at critical systems branching or bifurcation points, when rapid transformation of a whole system may occur.

For example, Eldredge and Gould propose that rather than always proceeding in gradual upward stages, evolution consists of long stretches of equilibrium, or lack of major change, punctuated by evolutionary branching or bifurcation points when new species spring up on the periphery or fringe of a parental species' habitat. And even though there are obvious differences between the branching off of new species and shifts from one type of society to another, as we shall see, there are startling similarities to Gould and Eldredges' model of "peripheral isolates" and the concepts of other evolutionary theorists in what has happened and may now again be happening in our cultural evolution.

The contribution of feminist scholarship to a holistic study of cultural evolution -- encompassing the whole span of human history and both halves of humanity -- is more obvious: it provides the missing data not found in conventional sources. In fact the reevaluation of our past, present, and future presented in this book would not be possible without the work of scholars such as Simone de Beauvior, Jessie Bernard, Ester Boserup, Gita Sen, Mary Daly, Dale Spender, Florence Howe, Nancy Chodorow, Adrienne Rich, Kate Millett, Barbara Gelpi, Alice Schlegel, Annette Kuhn ... to name but a few. Dating from the time of Aphra Behn in the seventeenth century and even earlier, but only coming into its own during the past two decades, the emerging body of data and insight provided by feminist scholars is, like "chaos" theory, opening new frontiers for science.

Though poles apart in origin -- one from the traditional male, the other from a radically different female experience and worldview -- feminist and "chaos" theories in fact have a good deal in common. Within mainstream science both are still often viewed as mysterious activities at or beyond the fringe of the sanctified endeavors. And in their focus on transformation, these two bodies of thought share the growing awareness that the present system is breaking down, that we must find ways to break through to a different kind of future.

The chapters that follow explore the roots of -- and paths to -- that future. They tell a story that begins thousands of years before our recorded (or written) history: the story of how the original partnership direction of Western culture veered off into a bloody five-thousand-year dominator detour. They show that our mounting global problems are in large part the logical consequences of a dominator model of social organization at our level of technological development -- hence can not be solved within it. And they also show that there is another course which, as co-creators of our own evolution, is still ours to choose. This is the alternative of breakthrough rather than breakdown: how through new ways of structuring politics, economics, science, and spirituality we can move into the new era of a partnership world.

~~~~~~~

by Riane Eisler

"The most important book since Darwin's Origin of Species." -- Ashley Montagu

"Validates a belief in humanity's capacity for benevolence and cooperation in the face of so much devastation." -- San Fransisco Chronicle Book Review

"As important, perhaps more important, than the unearthing of Troy or the deciphering of cuneiform." -- Bruce Wilshire, professor of philosophy, Rutgers University